Real Estate

Everything You Need to Know About Source of Income Discrimination

By Emma McAleavyNovember 4, 2020

This article was written in collaboration with Mike Parello. Mike is a housing advocate, writer and organizer with experience supporting tenants in accessing safe, long-term housing in Massachusetts and New York City.

For over seventeen years, Karla (a pseudonym) used her Section 8 housing voucher to pay for part of the rent on a three-bedroom house in Cypress Hills, Brooklyn. She raised four children there while working as an administrator for a union. In December, however, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA)—the government body administering Karla’s voucher—let her know her rent would be increasing. Several of her children had grown up and moved out, decreasing her family’s size and consequently her voucher amount. She would no longer be able to afford her home. Not only that, but Karla was facing domestic violence at home.

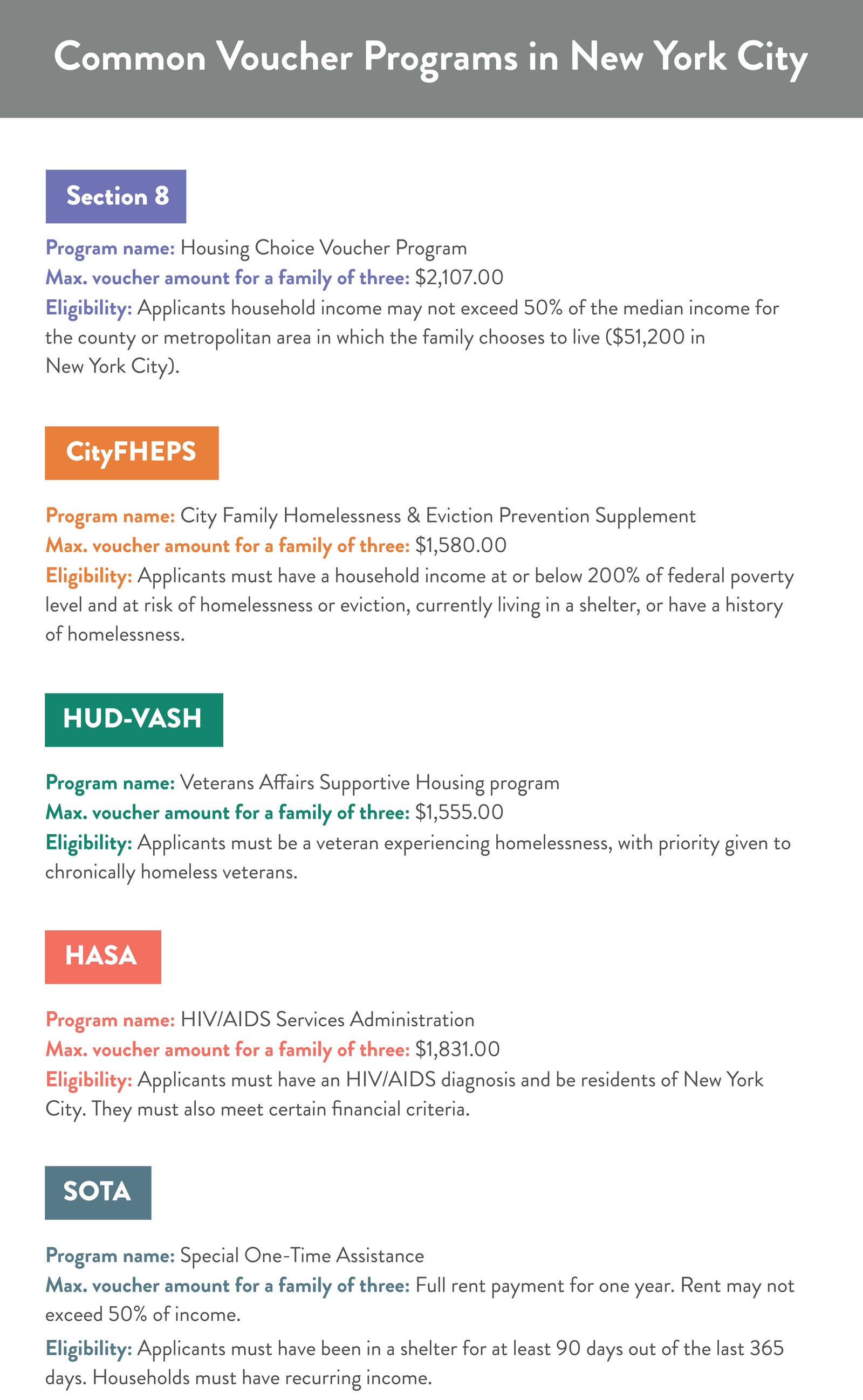

Housing vouchers, like the Section 8 housing voucher Karla has, are a form of government rent assistance that provides stability to low-income tenants. Some voucher programs are specifically for veterans, individuals experiencing homelessness or people living with HIV/AIDS. Voucher programs have been shown to reduce homelessness and are linked to improved health and education outcomes for children. Unfortunately, even after successfully applying for and receiving a voucher, voucher holders often struggle to find housing because landlords are unwilling to extend leases to them.

Karla may have experienced this discrimination first-hand. Although she was diligent in her efforts, she was frequently met with ambivalence or vague assurances that her call would be returned when she reached out to landlords or realtors. The process was made more complicated by the fact that she began looking for a new home around the same time she moved into a shelter for women experiencing domestic violence.

Frank Olesko, an investigative coordinator for Fair Housing Justice Center, says it’s common for voucher holders to struggle to find housing. The act of refusing to accept a tenant with a voucher is known as source of income discrimination and is illegal in New York State. But some tenants are still explicitly told that a landlord doesn’t accept vouchers. More frequently though, landlords and realtors use evasive tactics like those Karla experienced, to avoid extending an application or lease to a voucher holder. “After the prospective tenant mentions their voucher they often hear, ‘Well, I’m not sure, I need to check with the landlord and see.’ And then they never hear from the landlord again,” Frank explained.

Photo by Fair Housing Justice Center

Frank’s job is to investigate this kind of behavior to uncover discrimination. Actors and fake applications are used to conduct these undercover investigations and prove bias. For example, if you think you may have experienced discrimination as a voucher holder, Frank can prepare an application for a prospective tenant who is identical to you in every way, except that they do not have a voucher. If the landlord accepts or responds to that fabricated applicant, that can help prove discrimination in court.

For landlords, the reasons for not wanting to rent to a voucher holder vary. Landlord’s may be unaware of the benefits of renting to voucher holders (namely a guaranteed and stable source of rental income paid by the state), and wary of the administrative burden of working with voucher holders. The process for leasing a space to a voucher holder is different than for someone without a voucher. The agencies administering the voucher require additional inspections when renting to a voucher holder. Based on the outcome of those inspections a landlord may be required to make repairs to the space and modifications to accommodate individuals with disabilities. Because the local housing authorities can be slow and difficult to work with, landlords have concerns about costly delays. But housing voucher advocates say that the long-term stability of tenants with vouchers, and the security of knowing most of the rent will be paid for by the government, makes up for the upfront administrative burden.

Voucher holders face the unenviable reality that in addition to being discriminated against because of their voucher, they may be discriminated against because of their age, family size, race, disability or any number of other factors. Sometimes it seems as if a landlord is biased against someone because they have a voucher when in fact they are biased against a potential tenant for another reason. According to HUD’s most recent resident characteristic report, voucher holders are predominantly people of color, making race-based discrimination a common confounding factor that works against voucher holders of color. Voucher holders like Karla, who is black, may not know if they are being discriminated against because of their race or because of their voucher. And sometimes the voucher itself can put applicants at a risk for other forms of discrimination. In particular, HASA voucher holders—HASA stands for HIV/AIDS Services Administration—may experience discrimination because of their status as a person with HIV or AIDS. “The title itself can be very detrimental to their ability to find housing,” Frank said of the HASA vouchers holders. “That’s very problematic.”

Because of all of the potential factors at play, the Fair Housing Justice Center often investigates several types of discrimination for a single complaint. When they find discrimination they refer the complainant to the legal resources necessary to bring a lawsuit at the state or federal level. These lawsuits, Frank says, act as a form of enforcement and deter landlords from discriminating in the future.

Whatever the landlord's objections, the experience of searching for housing can be draining for voucher holders. Madeline Bacchus is an intake and outreach specialist at Fair Housing Justice Center, and works directly with voucher holders who are experiencing discrimination. “I do get people who just break down over the phone crying,” she said. “It is really important for people who are stuck in this situation to not put so much blame on themselves for the difficulty of finding housing. It is not them, it is not a personal failure. There are so many different things working against them.”

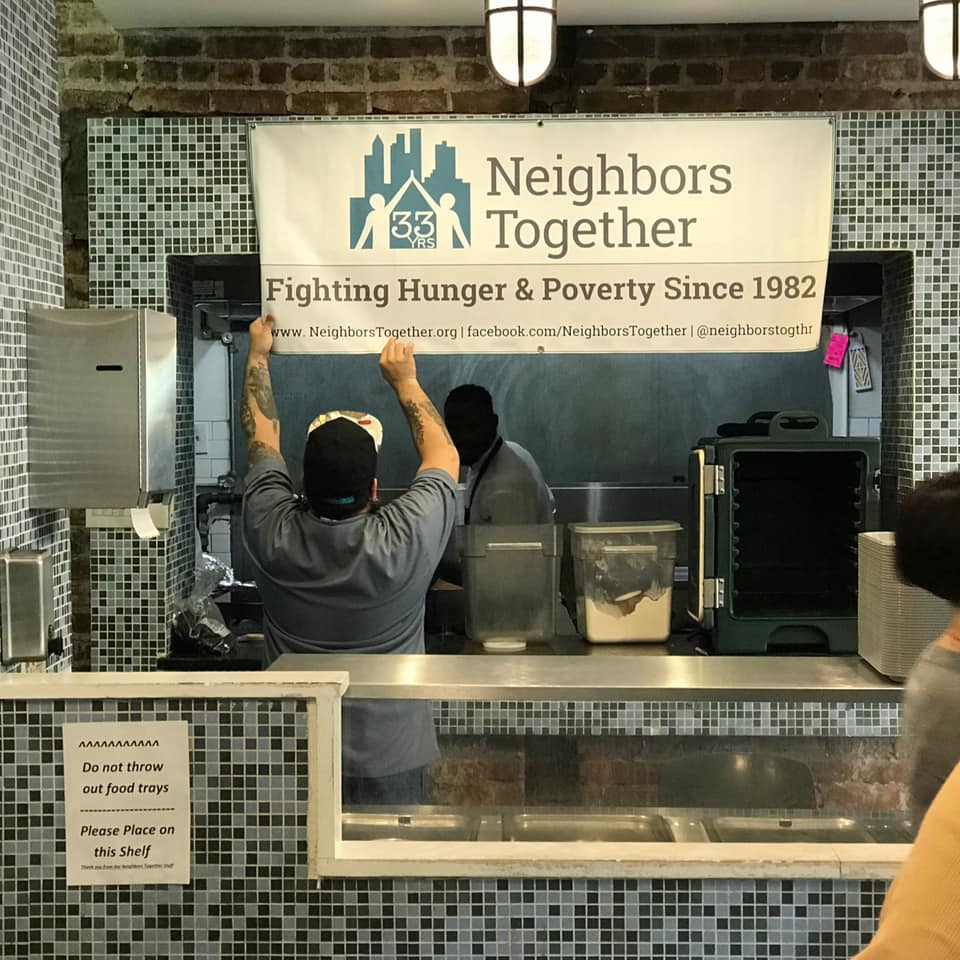

Photo by Neighbors Together

Fortunately, there are resources available to help voucher holders seeking housing. For people who are experiencing source of income or other forms of housing discrimination, it’s important to seek out help. That’s what Karla did. After months of fruitless searching, she reached out to Neighbors Together, a nonprofit agency that works with voucher holders to recognize and combat source of income discrimination.

“They actually sit with you while you’re making the phone call and guide you.” Karla said of the help she received from Neighbors Together, “They encourage you not to answer questions the landlords shouldn’t ask you.” That support was invaluable. Without it, Karla said, she thinks she would have given up.

Karla’s hard work eventually paid off. In mid-March, just as New York City began to shut down in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, she was notified by email that her application for an apartment through Housing Connect, an online portal for applying for affordable housing, was selected for further processing. In July, after spending seven months in the shelter, Karla moved into her new studio apartment.

It was a big transition after seven months in a shelter with other women, and seventeen years of living with her family before that. She has had her moments of doubt, wondering if she made the right decision to strike out on her own and move into a studio. But on the whole, she says she’s relieved to finally be in a space of her own. She’s been retired for a few years now and spends her time in her new studio cooking her specialties, including barbequed chicken and macaroni salad. She says her granddaughter (who is “seven going on twenty-one”) has visited her new apartment and approves. Karla is looking forward to taking care of her granddaughter while she does remote school. Mostly, though, Karla is using the time to rediscover herself. “I have to find me. That’s what I’m doing now, finding out who is Karla now?” she said. “I’m getting positive answers,” she added.

Photo by Mayela Rodriguez

What to do if you think you might be eligible for a voucher

If you think you might be eligible for a housing voucher consult with staff at your local homebase office. These centers are designed to help you develop a personalized plan to overcome an immediate housing crisis and achieve housing stability. You can also apply for other entitlement programs like SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or food stamps) at your homebase office. Your homebase office may be operated by a nonprofit organization in partnership with the city.

What to do if you have a voucher but are struggling to find housing

Neighbors Togethers, a nonprofit organization in Bedford-Stuyvesant and Brownsville has a guide of tips for voucher holders. The Osborne Association in the Bronx works with families and individuals affected by the criminal justice system and has programs specifically for helping meet housing needs. BronxWorks can help residents of the Bronx access housing benefits. Women in Need works directly with women and single mothers to provide housing support throughout New York City. Housing Works, meanwhile, offers housing support to people living with HIV/AIDS.

What to do if you think you’ve been discriminated against because of your voucher

If you think you’ve been discriminated against as a voucher holder, you can contact the Fair Housing Justice Center to discuss your complaint. You can also file a complaint with the Law Enforcement Bureau of the New York City Commission on Human Rights. Keep in mind, though, that you cannot have an active case with both of these organizations.

What to do if you are a landlord who would like to proactively make your space available to voucher holders

Despite the prevalence of source of income discrimination, many landlords appreciate the long-term stability that comes from renting to tenants with housing vouchers. If you are a landlord with available units, you can learn more about the Owner Incentive Program through NYCHA. The Owner Incentive Program provides landlords with expedited inspections, exclusive listing opportunities, and electronic payment options to eliminate trips to the bank. You can also familiarize yourself with the Housing Quality Standards (HQS) set forth by HUD to prepare your unit for potential voucher holders. Additionally, the other nonprofit organizations mentioned above would doubtless appreciate being alerted to any spaces you have available for their clients.

Feature image by Marie Godeau Robinson

Emma McAleavy was Listings Project's Content Editor. During her tenure at Listings Project she brought the stories of our community to life on our blog and in our monthly newsletter. Emma’s writing has also appeared in The New York Times, Outside Magazine, and Architectural Digest.